Higher education professionals from across the world met in Stirling last month to discuss approaches to lean. Vincent Wiegel shares his reflections of an event attracting a growing number of delegates each year.

Lean higher education is gaining traction. Each year, growing numbers of delegates from the Americas, Australasia and Europe turn out for the Lean in Higher Education conference, which this year was held in Stirling – and what an utterly delightful and insightful event it turned out to be.

Content and form of the presentations varied from plenary presentations to hands-on workshops. A few were nicely provocative: for example, what if Disney ran your university?

Some might cringe at the idea of a commercially-driven university. But a presentation about Aberdeen airport nicely highlighted the customer-centric approach, from which universities would definitely benefit.

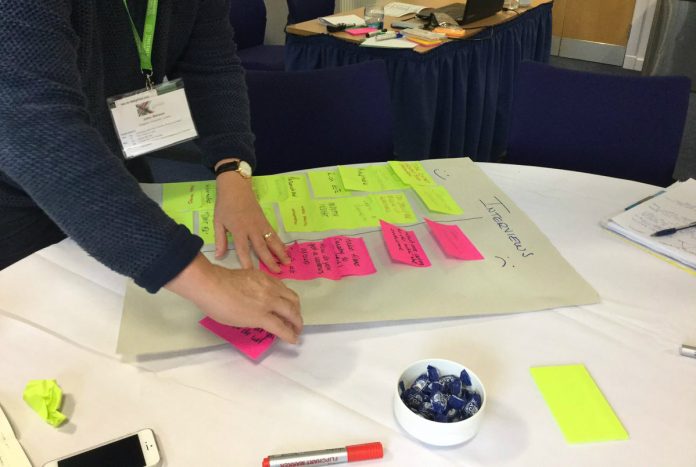

In the same vein, various presentations highlighted the cultural aspect of lean and of running an university, making the theme ‘people, culture and lean in higher education’ come to life. Some focused on measuring the effect of lean HE projects and the transfer of knowledge. The benefits exploration map produced by the University of Strathclyde as a part of the approach to evidencing the lean benefits in higher education struck me as powerful, yet simple.

A counterpoint from traditional academics would have enriched the event even further. The lean HE community, as it develops, shares an enticing vision of what lean education would bring, but it is still a minority voice. Bringing others on board, in particular researchers and teachers, would be a valuable objective for the coming years.

What struck me from the panel discussion is that the debate isn’t yet closed on what lean means for higher education, or the best way to do it.

Opinions were divided in the room between the panel members and delegates on many of the discussions we had. One of the key questions in the debate centred on whether universities needed a ‘lean team’ to start their journey.

The panel, drawn from European and US expert practitioners, were convinced that full time staff dedicated to lean were not required. The audience disagreed, with the voting app we used indicating that conference attendees were steadfast in their belief that staffing is critical to embedding lean.

Perhaps there are two things we can learn from this. Firstly, that we have yet to learn the right way to implement lean for HE. That said, on reflection, in a sector as diverse as ours perhaps we never will find a ‘right way’ to implement lean, and furthermore perhaps this disagreement is healthy. Secondly, practitioners in the sector feel a real need for resources, especially in the shape of people, to bring the promise of lean to bear.

At this year’s event, organisation was smooth and tight without being stifling, and the Stirling team did a great job. Conferences can be a bit of a long haul, but not this one – it was learning lean in a lean way.

In addition to the known practitioners and researchers, a lot of first-time delegates were welcomed. This is very encouraging. The years of effort put in by the Lean HE steering group are now paying off.

Lean HE is still a young domain. The Companion to Lean Management published by Routledge provides an up-to-date overview of lean with three full chapters on lean and education. That is encouraging, but the road ahead is still long and it needs more fellow travellers still. So I would encourage everyone to attend the next Lean in higher education conference in Sydney, Australia.